Machine Learning for Discovery of Ultrahigh Capacitive Energy Storage Materials

- Course: EECS 349 Machine Learning, Professor Doug Downey, Spring 2018, Northwestern University

- Team members: Benjamin Warren (Junior, Materials Science/Computer Science)

- Contact: benjaminwarren2019@u.northwestern.edu

Note: The machine learning described here was used to support my Materials Science and Engineering 390 design project on ultra-high capacitive materials discovery, which further explored theory and design strategies for UH capacitive materials development. Crossover between the projects was approved by both Prof. Downey and my mat sci professor.

Abstract

As recent materials research has shifted focus toward technologies for efficient energy storage and distribution, special attention has been paid to the furtherance of high energy density capacitors, which have excellent versatility and already have broad applications in solar cells, pulsed power systems, and railguns, among others. Anti-ferroelectric (AFE) dielectric materials are considered particularly good candidates for further development of ultracapacitive systems due to their high energy storage densities and low losses. Identification of promising novel AFE dielectrics is a significant first step towards meeting modern global energy demands.

Our task was to roughly predict the energy storage density of a large number of novel antiferroelectric dielectric materials based on their chemical and structural properties. A large training dataset of known dielectric materials was compiled from multiple materials databases, and tens of machine learning regression models were trained to predict “figure of merit” κEg2, which is proportional to energy storage density, using 23 derived chemical properties as features. We found the most reliable model using a RandomForest learner, which gives correlation coefficient = 0.5703 and relative absolute error = 71.85%. Evaluation against a test set of procedurally generated novel materials suggests NaTaF3, NaNbF3, and NaHfO3 as good candidates for experimental evaluation. We conclude by discussing lessons from the machine learning and outlining a multilevel computational approach for materials discovery.

Motivation

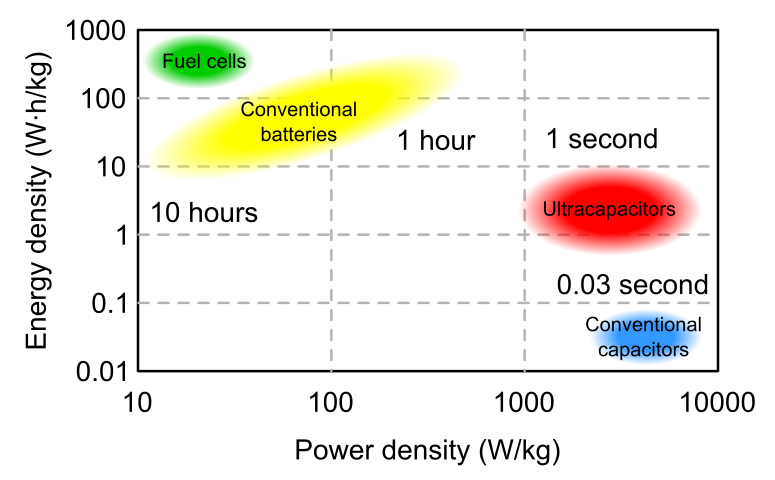

Ultrahigh capacitive materials (also called ultracapacitors or supercapacitors) fill a special niche in the realm of energy storage technologies. That’s because they exhibit not only the high power densities typical of conventional capacitors, they also can store moderate energy densities, which allows them to serve a variety of functions including power buffering, voltage stabilizing, high-speed device charging, and more.

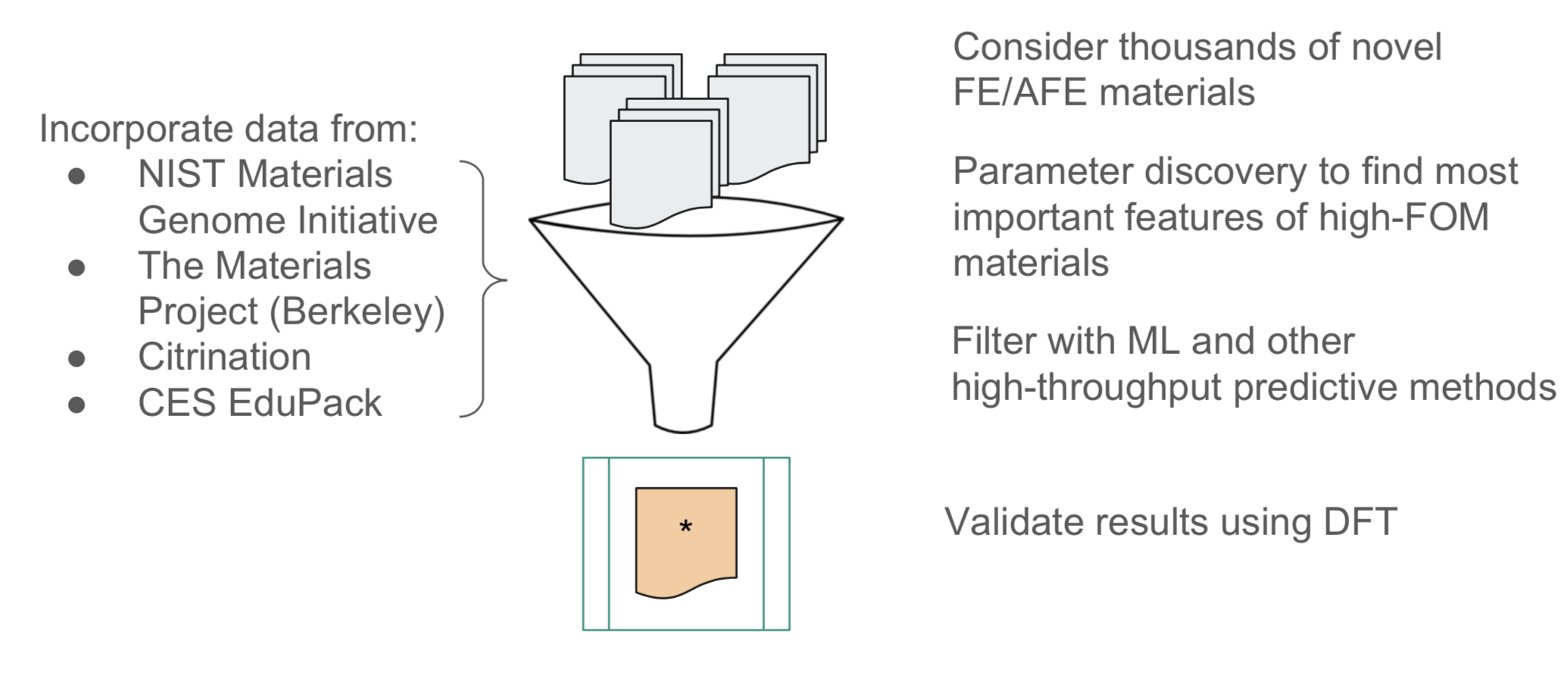

We are highly interested in finding novel ultracapacitors with even higher energy storage densities. However, experimentally determining electrical properties is very tedious, and even approximating electric properties using a quantum-mechanical (density functional theory) calculation is highly computationally intensive and can take hours per material. If we wish to examine thousands of potential materials, neither of these options is feasible. Therefore, we can improve our approach by instead using a machine learning model to make high-throughput predictions of energy storage density, the best of which can then be experimentally validated. This is a relatively new approach in the field of materials science, so any positive results may serve as a helpful proof-of-concept.

Background

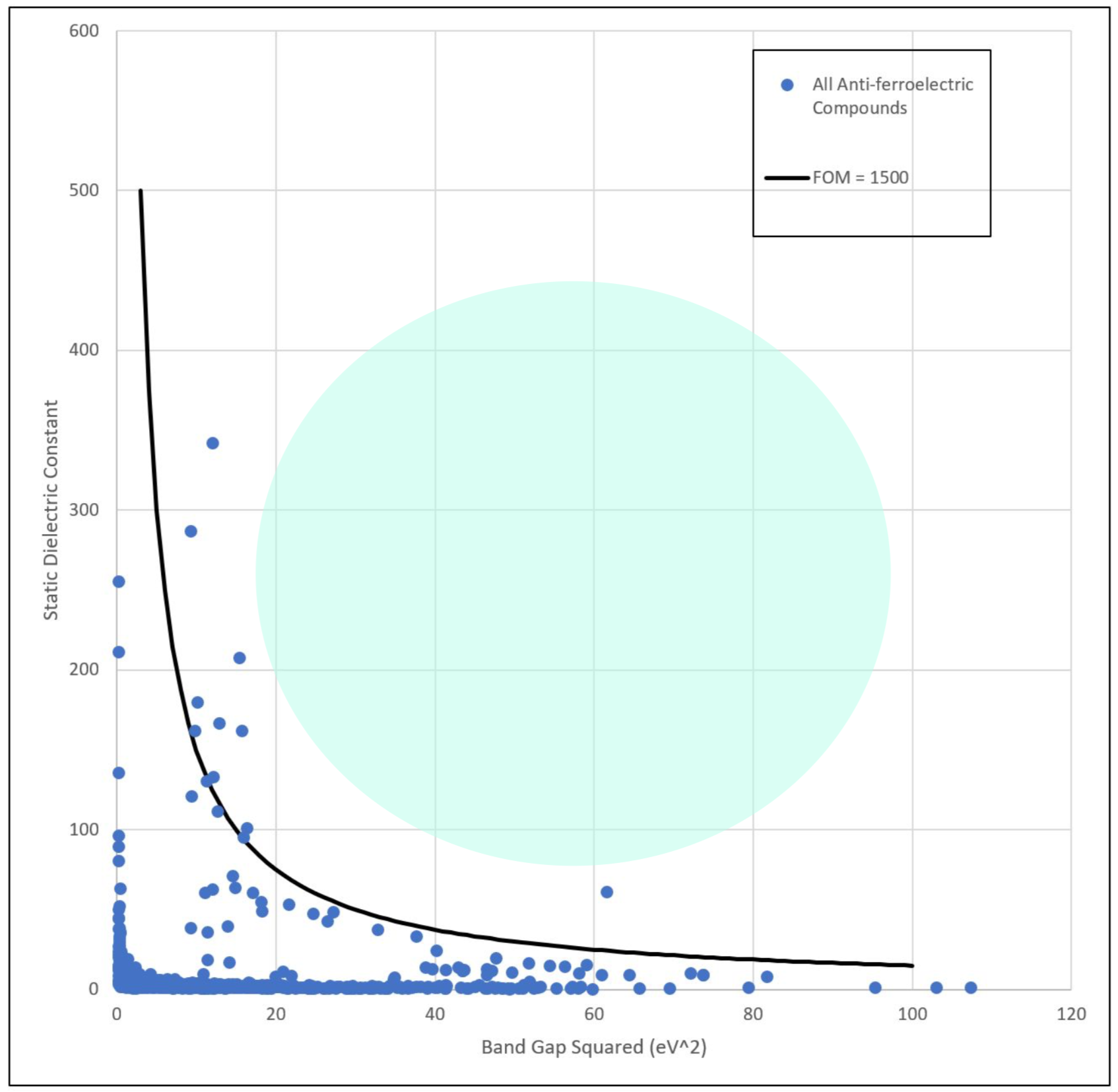

The energy storage density, U, is proportional to two materials properties of the dielectric: the dielectric constant, κ, and the square of the band gap, Eg. In other words, we can define a desired figure of merit FOM = κEg2 ~ U, for which we wish to achieve the maximum value. Large U is difficult to find in practice because κ and Eg are competing quantities.

In particular, Anti-ferroelectric (AFE) dielectric materials are considered particularly good candidates for further development of ultracapacitive systems due to their high energy storage densities and low losses. The the majority of AFEs have a perovskite lattice structure with chemical formula ABO3, where A is a monovalent or divalent metal, B is a transition metal, and O may occasionally be replaced by F, Br, or Cl. Because these are the most common high energy storage materials, our focus in this initial machine learning exploration is the prediction of promising novel AFE materials. In the future, this may serve as the basis for similar explorations focusing on other material structures.

Data Acquisition

Good data collection is one of the most challenging parts of creating a model for scientific property-predictions. That’s because while we would like all of our training data to be measured in consistent ways, different papers will inevitably use slightly different methodologies for determining electrical properties of materials. But since we needed a large dataset to make generalizable predictions, we couldn’t afford to be too picky; our best bet was to pull from large materials databases with standards on the data they aggregate.

Training Data: A NU MSE graduate student previously working on ultra-high capacitive materials had written scripts to pull data from various public materials databases including the Materials Project (Berkeley), Citrination, the NIST Materials Genome Initiative, and CES EduPack. He was able to provide those scripts to us, which allowed for the compilation of a training dataset of 1,218 dielectric materials with known Eg and κ. From this, we could calculate FOM = κ Eg2, which we chose as the target value for our ML regression models.

Test Data: As mentioned earlier, we are focused on making predictions for AFE materials, which commonly take the form of ABO3 perovskites. So, I wrote a python script to procedurally generate all potentially viable materials of this form. This gave approximately 1400 test materials.

Feature Selection

After conducting review of materials science literature, a team member in my materials design 390 and I determined 23 chemical property features with relevance to the band gap and dielectric constant. These properties, listed below, were calculated for each training and test example by using a script to find the average and range of the property over the elements given in the chemical formula.

- Average… total number of unfilled valence electrons, row in the periodic table, Pauling electronegativity, number of s valence electrons, number of p valence electrons, number of d valence electrons, Mendeleev number, elemental work function, atomic radius

- Range… total number of valence electrons, total number of unfilled valence electrons, radius of s orbitals, radius of p orbitals, radius of d orbitals, Pauling electronegativity, number of unfilled p valence electrons, elemental work function, elemental polarizability, elemental crystal structure, Allred Electronegativity, first ionization energy, covalent radii, atomic radii

Although I was interested in finding ways to quantify lattice structure information into features, it ultimately proved to be too challenging for the time frame.

Initial Results

Test and training data was exported to .arff files for use in Weka. Then, regression models to predict FOM were made using each of the regression learners available in Weka and 10-fold cross validated.

Initially, the best learner appeared to be a multilayer perceptron model, which had a correlation coefficient = 0.6099 and a relative error = 74.9%. However, when this model was evaluated against test data, it was found to be strongly overestimating FOM for materials on the higher end. Since we are only interested in the highest-FOM materials, the initial best model was therefore uninformative.

Next, I wanted to test the influence of material structure on the predictive strength of the model. So, I created a subset of the training data including only those materials with a perovskite structure (the same structure as all of the procedurally generated test data). This subset contained only 92 materials. At this point, I also noted that many of the samples contained missing “range” features due to issues with missing data for some elements, so I experimented with the same learners after removing all of the “range” features. This tended to increase correlation and reduce error, likely because of a combination of noisy range attributes and curse of dimensionality. After extensive testing, the best obtained model for the subset data was from a Random Forest learner and gave 10-fold CV correlation coefficient = 0.5703 and relative error 71.85%. While this error looks fairly high, it is reasonable given the complexity of the learning task. The moderate correlation implies that our model should be capable of making reasonable, if rough, predictions.

Running this second-iteration model against test data gave results that were more closely aligned with my intuitive expectations for what highest and lowest predicted FOMs should look like. The three tested novel dielectric materials with highest predicted FOMs are given in the table below.

| Material | Predicted FOM |

|---|---|

| NaTaF3 | 1165.948 |

| NaNbF3 | 1116.847 |

| NaHfO3 | 1089.577 |

Interestingly, while the second iteration of models was run with far less training data than the first iteration (only 92 vs 1,218 examples), because the training data samples in the second set were more similar to one another and to the test data, the correlation and error for best-performing models were fairly similar. Additionally, the second-iteration best model appeared to give more realistic results.

Comparing our highest-predicted FOM values for novel compounds to FOM for existing AFE dielectrics, which can be seen in the plot below, we can see that our three best compounds, all having predicted values 1000-1200, are somewhat below our target value of FOM = 1500 for next-generation ultracapacitors. However, their predicted values are consistent with most existing ultracapacitors, and DFT evalutation may show better-than-predicted performance. Additionally, inclusion of dopants known to increase energy density may bring these materials into our target range. Thus, our discovered materials appear to show promise and merit further experimental evaluation.

Conclusion and Next Steps

While the three novel materials – NaTaF3, NaNbF3, and NaHfO3 – identified as potentially exhibiting high energy storage density have not yet had their energy storage densities validated with DFT or experimental testing, we note that Nb and Ta perovskites have been indicated in literature as demonstrating particularly high dielectric constants (https://aip.scitation.org/doi/abs/10.1063/1.1558205), which lends credibility to our model results.

The fact that our best performing learners were multilayer perceptron and random forest means that these models are not very interpretable. However, one thing that is certainly clear is that energy storage density derives from a complex network of relationships between both chemical and structural materials properties.

In the future, these models could be improved upon by the addition of a variety of features to represent lattice structure of a material, as well as refinement of the chemical features used. For further improvement in feature selection, one good option might be greedy feature insertion. Additionally, obtaining more training data would, as always, improve model performance.

In sum, this project can serve as a proof-of-concept for how machine learning might be applied to materials discovery and design. In this multilevel design process, high throughput machine learning methods are applied as an initial filter, followed by validation by more rigorous computational methods (such as DFT), and then only the computationally validated compounds are actually synthesized and experimentally tested. When sufficient quantities of training and test data are available, this cuts back dramatically on the amount of time required to produce viable solutions.